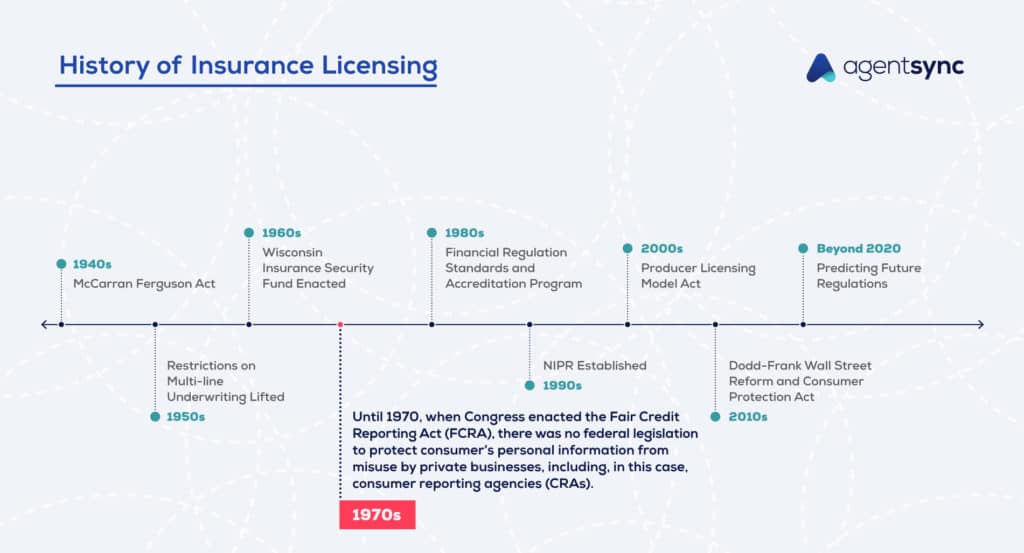

The 1970s are remembered by more than just bell-bottom jeans and tye-dye shirts, within the insurance industry, at least.

Whereas the 1960s saw many, many regulatory changes, the ‘70s were marked by just a few very notable ones: the Fair Credit Reporting Act and the introduction of separate male and female mortality tables.

Congress enacts the Fair Credit Reporting Act

In today’s digital age, we’re all familiar with the need for consumer data protection. After all, the irresponsible collection, use, and storage of consumer information by companies can result in devastating breaches of privacy and real financial consequences for consumers. But until 1970, when Congress enacted the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), there was no federal legislation to protect consumer’s personal information from misuse by private businesses, including, in this case, consumer reporting agencies (CRAs).

CRAs collect and use consumers’ personal information – “credit history and payment patterns, as well as demographic and identifying information and public record information (e.g., arrests, judgements, and bankruptcies)” – to create a consumer report (also known as a credit report). These reports can then be used by insurers, employers, landlords, lenders, utility companies, and government agencies when making decisions about whether or not to engage in business with those consumers.

Credit reports can have an outsized impact on a person’s life. So, it’s really important that the information in the report is accurate, well-protected, and used for the right reasons. But that isn’t always the case.

In the 1960s, there was rampant abuse of consumer data within CRAs. Reports of the misuse of data included the collection of lifestyle habits – sexual orientation, marital status, drinking patterns, cleanliness – the outright fabrication of negative information, and unauthorized data sharing with law enforcement. At the time, consumers had no right to see, verify, or challenge the information being used in their credit reports.

This predatory behavior led directly to the passage of the FCRA, which introduced many protective measures, including the consumer’s right to access a free copy of their own credit report and challenge any incorrect information.

Since its inception, the FCRA has seen a number of iterations. But the work isn’t over. In a recent study conducted by the Federal Trade Commission, nearly a quarter of consumers identified and challenged inaccurate information found within their credit reports.

Separate male and female mortality tables first introduced by the NAIC

Remember the 1960s, when we learned about how an annuity payout rate considers an annuitant’s mortality risk?

Well, to determine a mortality risk, life insurance companies rely on mortality tables.

Mortality tables – also known as life tables or actuarial tables – show the estimated likelihood of death for a given population within a given year. When calculating the risk of death, modern mortality tables take a number of factors into account, including a person’s age and gender. But mortality tables need to be updated every ten years to more accurately demonstrate death rates by reflecting changes that can impact a person’s risk of death, such as a reduced likelihood of death due to advancements in health care or, conversely, increased likelihood of death due to pandemics and war.

Insurance companies rely on these mortality tables when building insurance policies, so, by regulating and updating these mortality tables, the insurance industry can prevent the inaccurate pricing of policies.

In the 1970s, the NAIC began the process of reviewing its model legislation on life insurance. Up to this point, mortality tables were unisex and gender-merged in that they combined the mortality rates for men and women. However, in reviewing the existing mortality tables, the NAIC came to the conclusion that maintaining a unisex mortality table would result in the need for insurance companies to manage deficiency reserves to cover losses emerging from the variance in male and female life expectancy.

But the emergence of separate mortality tables for men and women isn’t necessarily a coup for the insurance industry. While the male and female mortality rates help insurance companies manage reserves and more accurately price premium rates, it also sheds light on sex discrimination within the industry. Insurance companies were found to charge women higher rates for the same coverage as men and even restrict the availability of some insurance policies.

The risk of discrimination from separate mortality tables caused such an uproar with state regulators that some deemed their use illegal. For instance, the 1975 ruling Henderson v. Oregon, a District Court held the use of separate mortality tables illegal in the state of Oregon.

Beyond the 1970s

Regulatory changes within the insurance industry are both historic and ever-evolving. It can be more than a full-time job to keep on top of which ones apply to your organization when managing regulatory compliance.

This is just one of several articles we have on the history of insurance regulation. For more fun facts and historical whodunits, check out the rest of the articles in our History of Insurance Regulation series.

To keep up with the regulatory changes that are happening now, see how AgentSync can help.