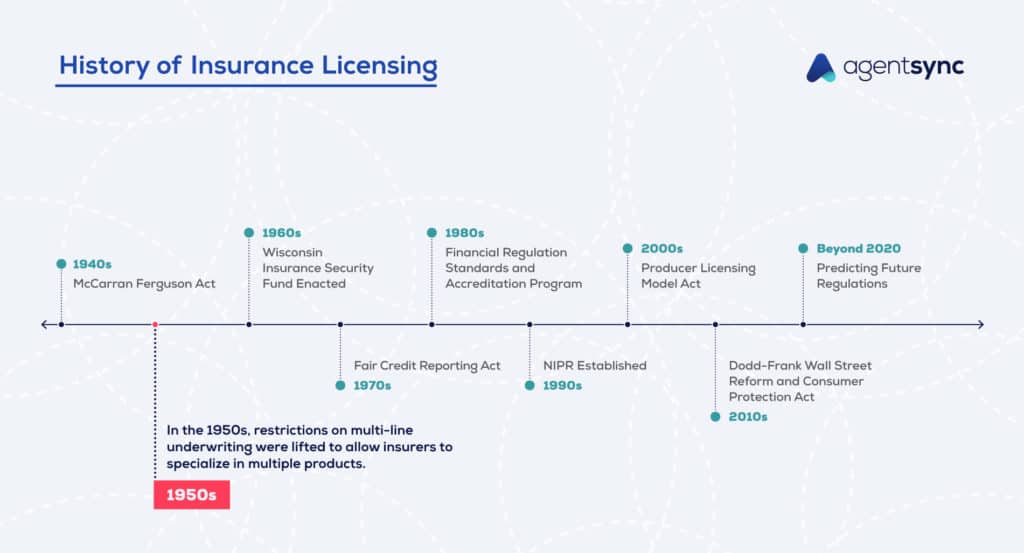

While the 1940s were largely defined by establishing the insurance regulatory framework, the 1950s were defined by reviews of that framework.

As with any industry, if a system isn’t efficient at scale or doesn’t support those it’s meant to protect, then it needs to change. The McCarran-Ferguson Act and the Unfair Trade Protections Act were designed to safeguard consumers against dangerous corporate behavior. Still, it’s always important to critically analyze the effectiveness of those systems and revise if necessary.

Additionally, the ‘50s saw the emergence of multi-line carriers, an important step in developing the insurance system that we have today. As state-based insurance gained footing, it became clear that state-specific regulation could impact competition between insurers within states. While at first, many states questioned a multi-line system, when some states began to adopt it, others followed.

State-by-state regulation: assessing its effectiveness

In 1958, Congress began investigating the effectiveness of state-by-state insurance regulation through the Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee of the Senate Committee. Senator Joseph O’Mahoney (Democrat, Wyoming), a principal lawmaker in creating the McCarran-Ferguson Act, led the investigation, which ultimately found state regulation lacking.

Early dissent for the McCarran-Ferguson Act centered around its inability to support and manage competition in the rate-making process. The investigation by Senator O’Mahoney seemed to confirm those fears.

The issue of rate-making comes down to the insurer’s ability to meet its financial obligation to cover risks as outlined within an insurance policy. Without insurance regulation, insurers could collect low premiums – to cut out competition – and default if risks are realized. By collecting such low premiums and failing to maintain the capital to cover risks as outlined in insurance policies, unethical insurers could force premium prices to go low, thus eliminating the insurers looking to collect the appropriate premiums to cover the actual cost of insurance.

The Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee was set up in the ‘50s due to reports that rating bureaus were stifling independent insurance companies. By price-fixing and setting prohibitively low rates for member companies, rating bureaus could prevent independent insurance companies from participating in the market.

But, as with most other insurance regulations, the impetus is on individual states to regulate rate-making. And, according to O’Mahoney and the Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee, the states weren’t doing enough to protect independent insurance companies.

This cycle of federal review and state response in insurance regulation continues today. It not only protects the state-based system of insurance regulation but also holds states accountable. Insurance regulation is designed to protect consumers from deceitful corporate behavior. While the states are best placed to manage that regulation, support and oversight from the federal government helps to create a national level of quality control.

The introduction of multi-line carriers

While hard to believe in today’s insurance landscape, U.S. insurers were historically only permitted to write a single line of business. However, in the 1950s, restrictions on multi-line underwriting were lifted to allow insurers to specialize in multiple products.

The ethos behind single-line insurance follows fairly closely to that of state-by-state regulation. The purpose was to allow insurers to specialize in the hyper-technical aspects of a given line of business. That way, they could become the go-to, the au-fait, the expert of all things specific to their line of business.

Beyond that, single-line insurance helped to demarcate underwriting requirements for the different lines. Reserve requirements for insurers changed based on their lines of business. And a rigid, compartmentalized insurance system where insurers could only offer a single line of business helped states manage the regulation of these requirements.

But the appetite for multi-line carriers was impossible to ignore. Consumers wanted bundled policies that would allow them to cover their broad risks through a single policy. Plus, insurers wanted to deliver. So, in 1943, the NAIC established the Diemand Committee – named after John A. Diemand, President of the Insurance Company of North America (INA) – to determine whether moving toward a system that allows for multi-line carriers could be in the public interest.

The answer from the Diemand Committee: It’s complicated.

Instead of recommending a break from the single-line system, the Diemand Committee suggested a more gradual adoption of broader underwriting expectations. At that time, many states were unsure of the advisability of a multi-line system. But, as some states began to adjust, insurers in the states that didn’t faced restrictive underwriting expectations and increasing competition from out-of-state multi-line carriers. By the late 1940s and early 1950s, every state adopted multiple-line underwriting to allow insurers to operate across lines of business.

Beyond the 1950s

Defined as a decade of revision and improvement, the 1950s show us that insurance regulation isn’t written in stone (except, of course, in the case of the Code of Hammurabi). As we look to future decades, we see that insurance regulation is fluid for a reason; as the society and people that it’s meant to protect change, so too must it change.

Regulatory changes within the insurance industry are both historic and ever-evolving. It can be more than a full-time job to keep on top of which ones apply to your organization when managing regulatory compliance.

This is just one of several articles we have on the history of insurance regulation. For more fun facts and historical whodunits, check out the rest of the articles in our History of Insurance Regulation series.

To keep up with the regulatory changes that are happening now, see how AgentSync can help.